Setting things up.

Why bother trying to attack a blockchain that's designed to be resilient when you could just pretend to be someone's grandchild? Well, in P2P (Peer-to-Peer) networks (a.k.a the wild-west of blockchain systems), gaining even a slight edge can result in massive profits.

That's why engineers working on a blockchain must pay attention to their P2P network.

Despite looking cramped and chaotic to some, P2P network dashboards typically reflect a network steadily making progress, albeit occasionally observing packet loss during monsoon season (yes, I've gotten woken up over stuff like this).

Occasionally, a dashboard hints at something more interesting, like the game of cat-and-mouse revolving around transaction gossip and MEV.

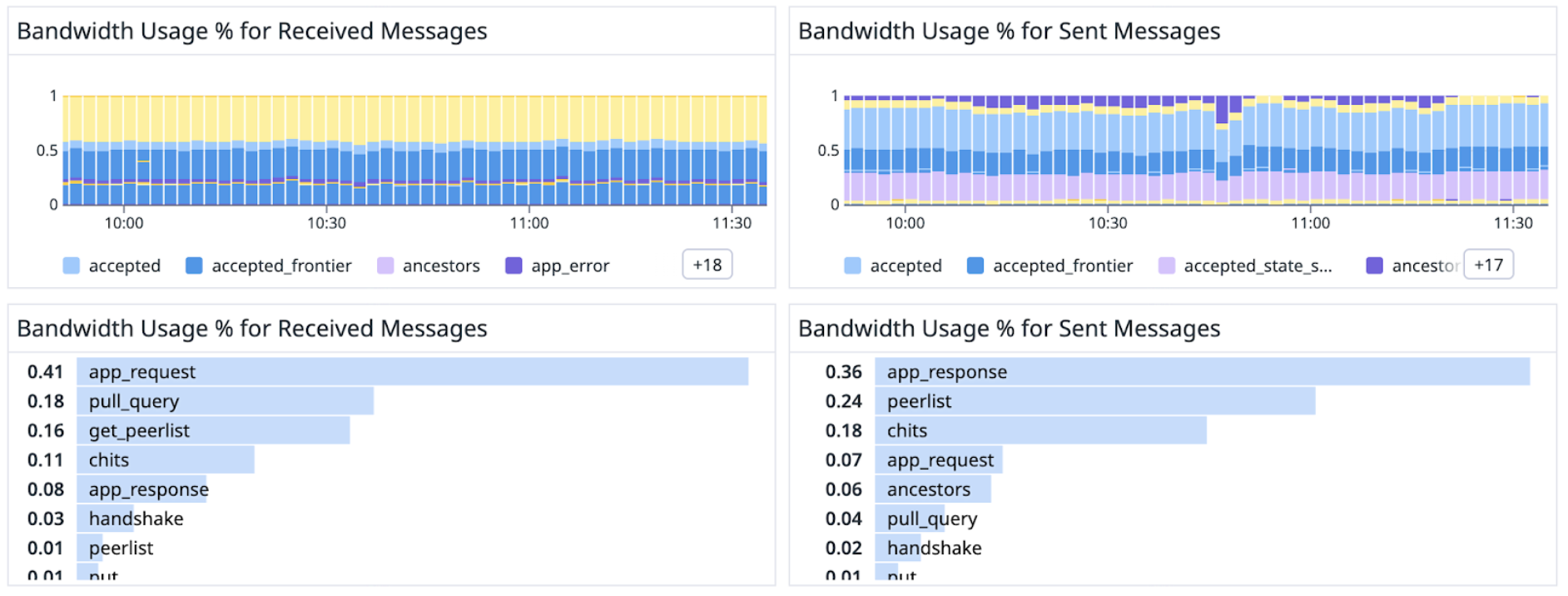

On a recent summer day, one of our monitoring dashboards showed an imbalance between the inbound and outbound volume of "app" messages—those used in Avalanche's transaction gossip layer. We were receiving significantly more requests than we were sending, and the responses we were sending back were consuming a suspiciously large portion of validator bandwidth.

At first glance, it wasn't clear exactly what was happening. Maybe our metrics were off. Maybe there was a bug in the networking logic. But the imbalance held over time, and the asymmetry was too big to ignore. Something was wrong.

A quick detour: How Avalanche gossip works.

Avalanche spreads transactions through a hybrid push–pull gossip protocol over its P2P network.

Push gossip: Newly issued transactions are pushed to validators across the network, especially those with more stake.*

Pull gossip: A validator periodically sends a Bloom filter describing its mempool to another uniformly sampled validator, who compares it with their own and responds with any new transactions.

The "pull" math is simple and powerful. Every validator samples uniformly once per second, so each validator should receive about one Bloom filter request per second.

When it comes to the rate of receiving a request from a specific validator, it depends on the size of the validator set:

- Fuji has ~100 validators, and Mainnet has ~1,000 validators.

- Fuji nodes are expected to get a request from a specific node every ~2 minutes

- On Mainnet, the expected rate is higher at ~17 minutes.

*Validators with more stake are prioritized because they're most likely to build the next block.

The unexpected behavior: It is always the C-Chain mempool.

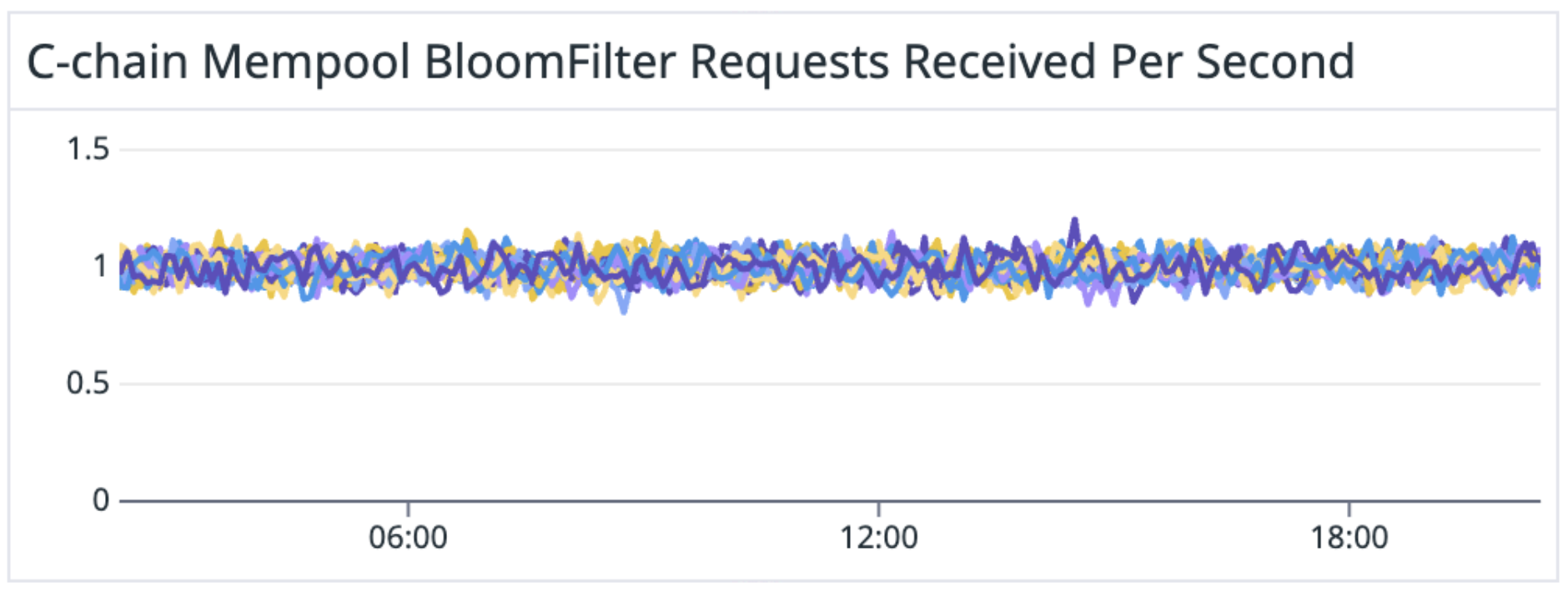

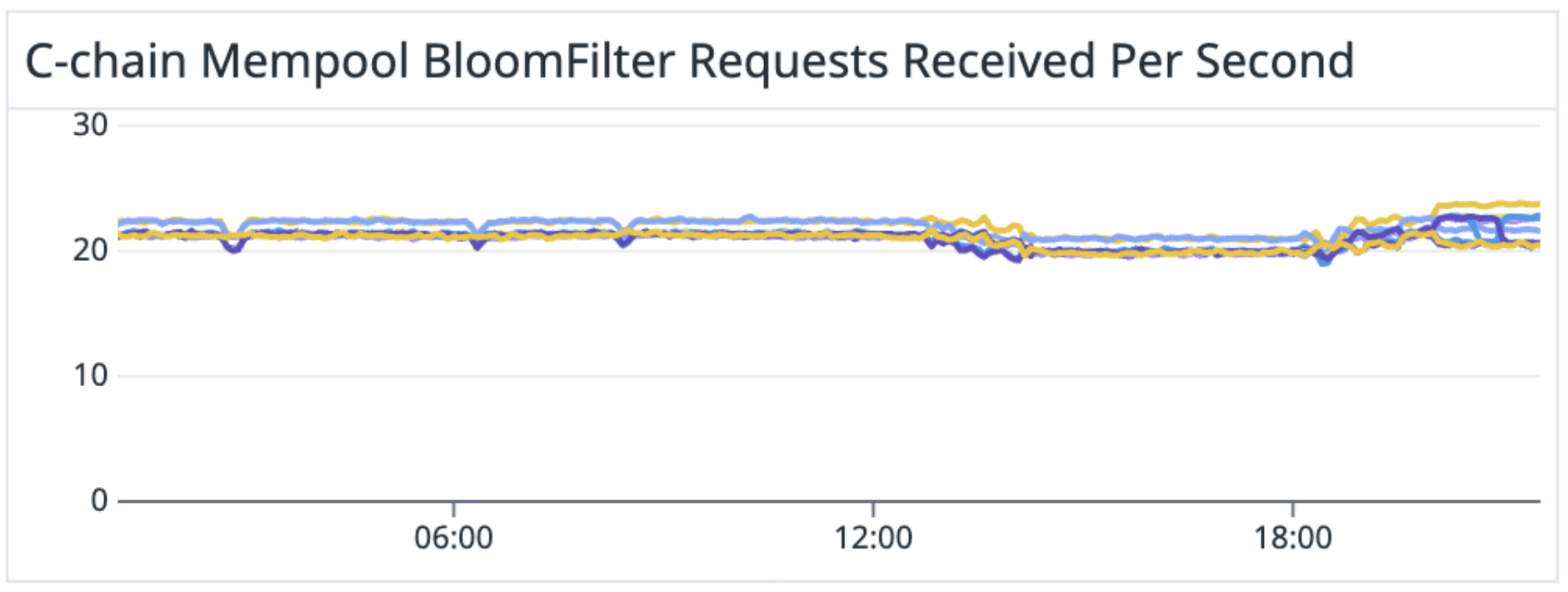

On the Fuji Testnet, these metrics behaved exactly as expected.

What we observed on Mainnet wasn't even close.

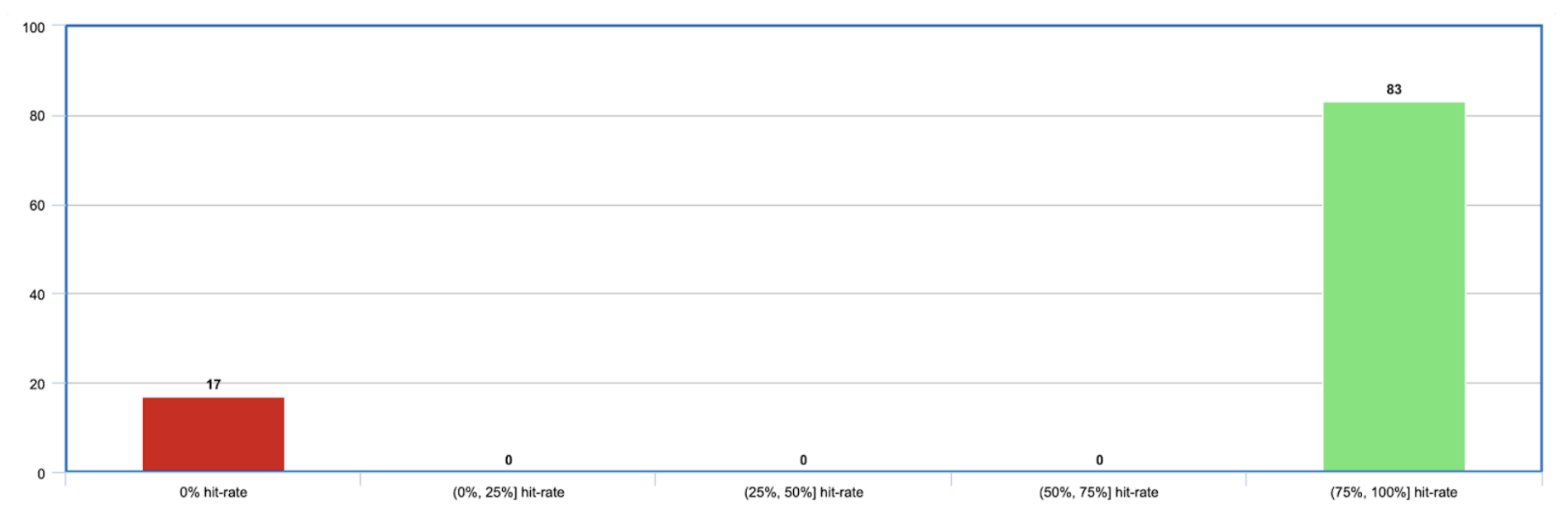

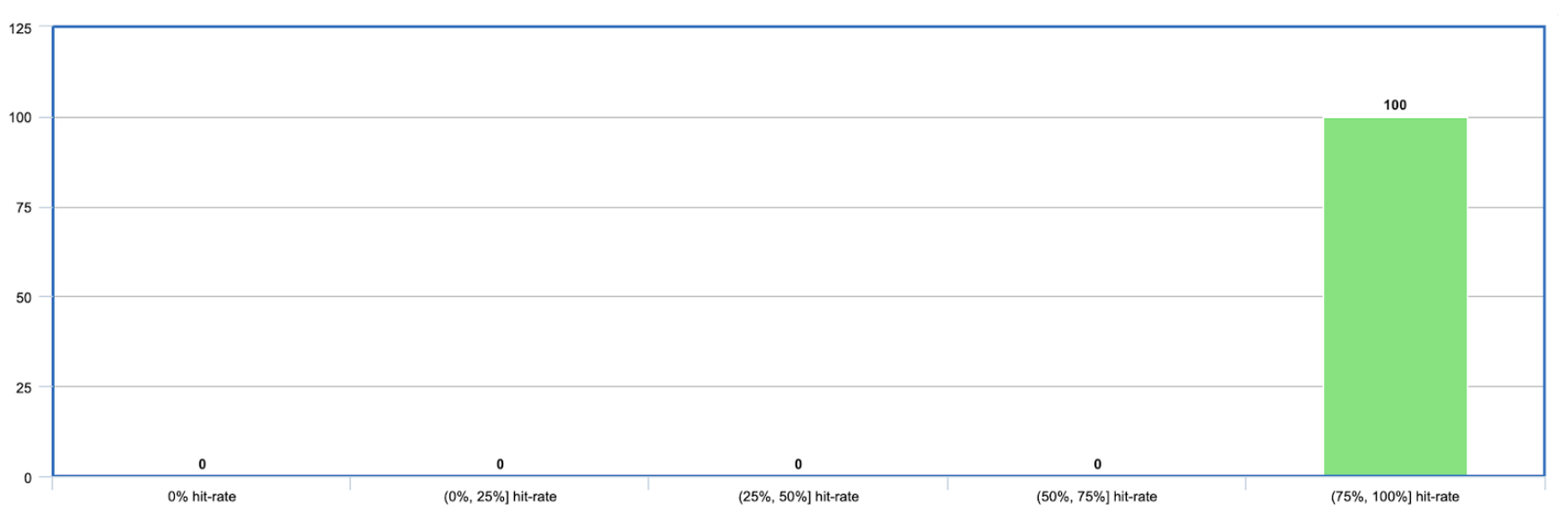

Our Mainnet nodes were consistently handling 20x the expected number of Bloom filter requests. Additionally, the hit-rates of the Bloom filters were bimodal—an anomaly not seen on Fuji.

While most requests had a high hit-rate (>75%), many requests had an abysmal 0% hit-rate. Almost no requests landed in-between.

This led to the suspicion that certain nodes were intentionally sending Bloom filters that didn't match any transactions in our mempool. That's like saying: "I don't have any of your transactions—send me everything you've got."

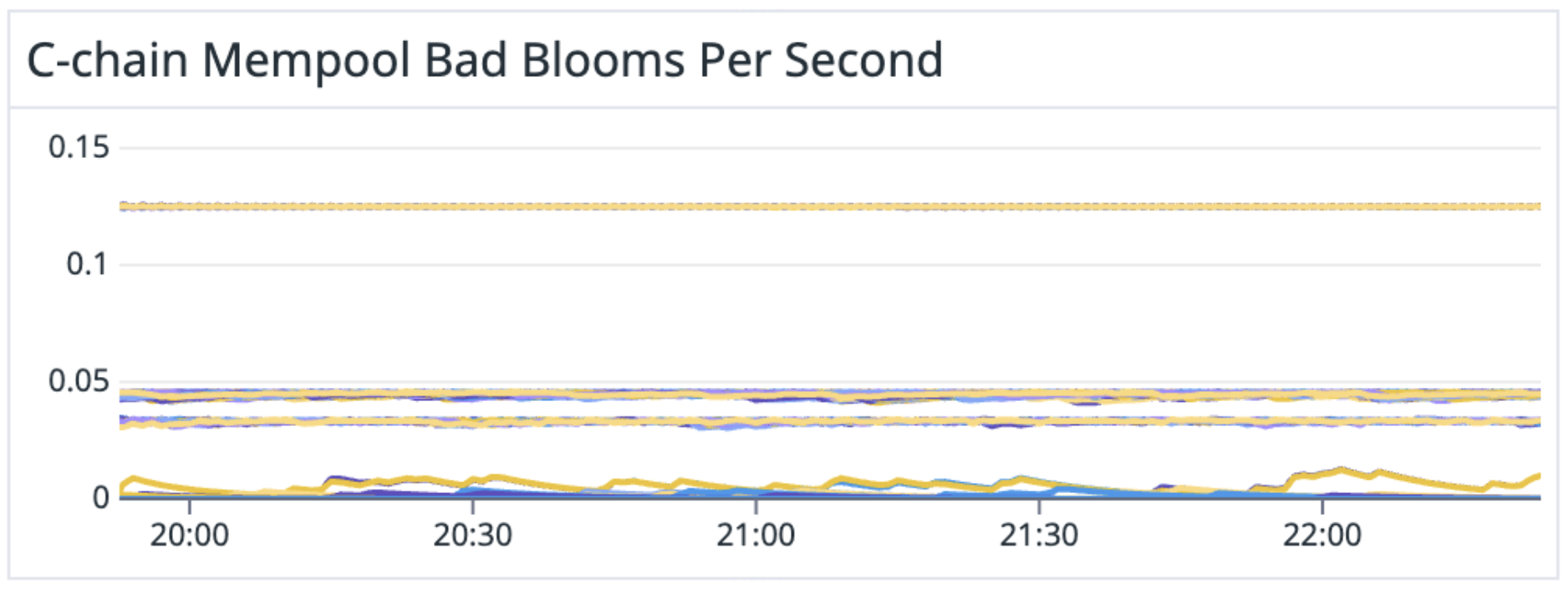

Intentional or not, they weren't sending bad Bloom filters once every 17 minutes (the rate at which a virtuous validator would). The worst offenders* were hammering the same validators with requests as quickly as every 8 seconds (0.125 bad Bloom filters per second).

This meant that targeted validators were repeatedly sending maximum sized responses—potentially hundreds of transactions at a time—to the same small set of peers.

Sending too many Bloom filters is one thing. Sending bad Bloom filters is unacceptable! We worked hard to optimize every CPU cycle of those Bloom filter checks! For THIS!?!? Unacceptable.

Interestingly, even non-validators have been asked for mempool information. While these nodes wouldn't receive the initial push gossip, they may have locally issued transactions in their mempools. Although, this could have just been an oversight in the modified implementation.

*Worst offenders:

- NodeID-MuEFvXvbZ964sk1rdQKWNtUc5PJAGkWeL

- NodeID-NHEESrJJNnyCPn5c5Uyp9EZYHCCkZwzuW

- NodeID-MZV1PpqVuFPa56t7TmfA8VVdXxDSHnQW7

- NodeID-LPf42gVqz97N6bogZGXJNTWhgBABEe4qE

- NodeID-3632EmwYracXebFyFTQvcEC7U6VREbPkZ

- NodeID-2KSietvSEq4mX2C8p1DAT83RTJPykxUqN

- NodeID-AyByRGSrfbDaeW4njEYwCzhsnMyZ2KMcw

- NodeID-8fq1H8oStMi9BZrEk8qiE8QAV7AtqGnXt

- NodeID-EtFG3SrbbudeFQCaWRxhwvv28wHpo8VRq

The Update: MOAR rate limits.

Avalanche already has a rate limit for Bloom filter requests, so what gives?

When the Bloom filter requests were originally added, the algorithm was slightly different. Rather than sampling a random validator every second, 10 validators were randomly sampled every 10 seconds.

This meant that a node should never see more than 2 requests every 10 seconds from the same node, even when accounting for time skew. As such, the rate limiting logic enforced this bound.

However, this sampling approach had two clear downsides:

-

Wasted bandwidth. Sending the same Bloom filter to multiple nodes made it likely that we would receive duplicate transactions.

-

High discovery latency. Sending requests every 10 seconds resulted in high discovery latency for nodes not included in the push gossip phase.

When changing to send one request every second we didn't make any changes to the rate limit logic. After doing some quick calculations, we can see that this was great for virtuous nodes and amazing for MEVers–our rate limit was hundreds of times looser than it needed to be.

The fix:

Instated probabilistic bounds. Instead of a flat cap, we now calculate the expected number of requests, and the variance, from the binomial distribution. On mainnet, this works out to about 10 requests per hour per peer while still ensuring that honest nodes will almost never get rate-limited.

Reinforce rate limits. Rather than immediately dropping rate limited requests, these requests are included in future rate limiting calculations. This enforces nodes to query no faster than the prescribed rate.

The results

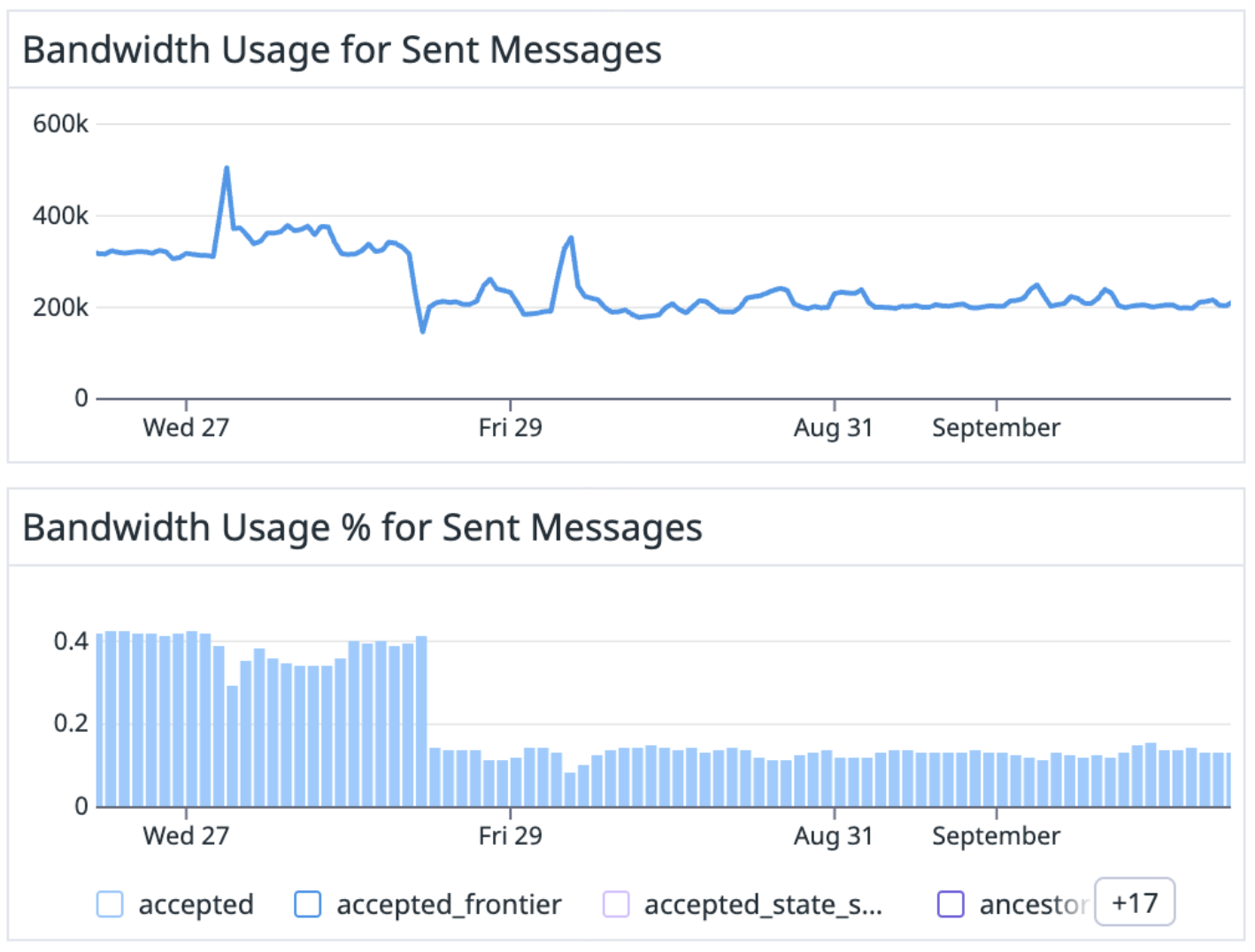

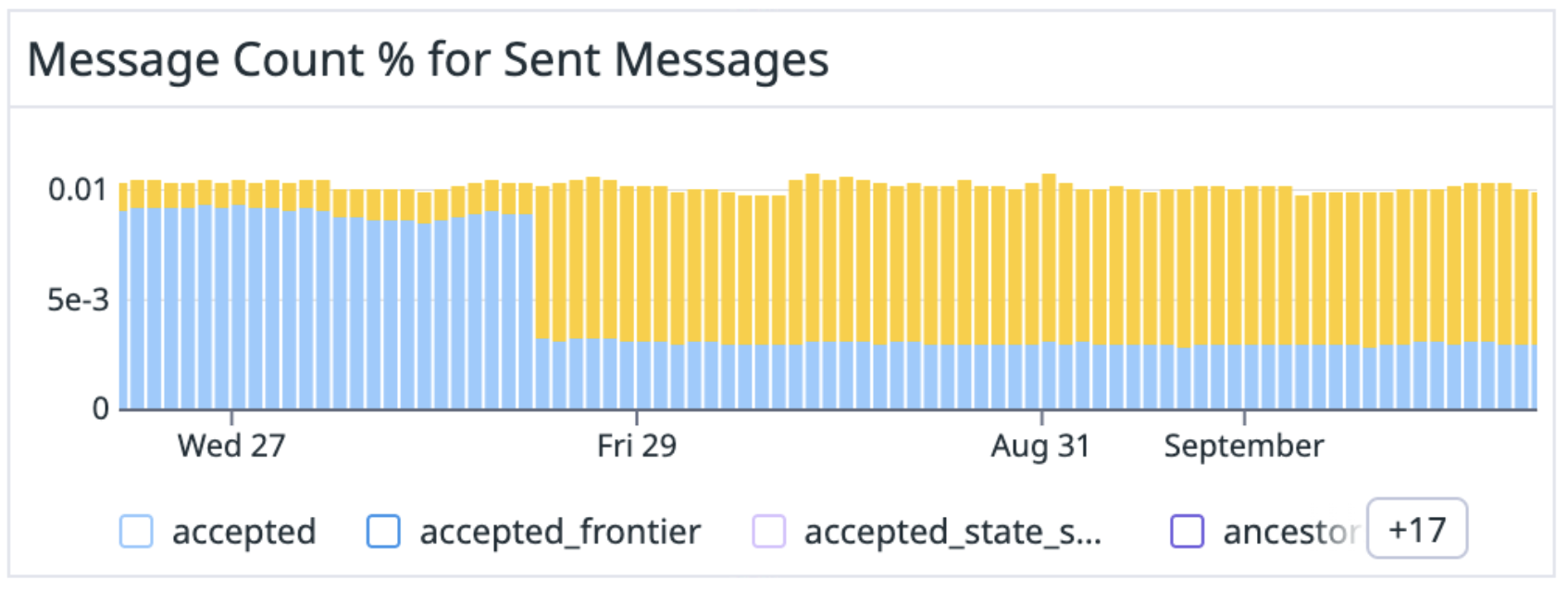

Immediately upon updating, our nodes reported a significant reduction in outbound bandwidth.

By enabling the improved rate limiting, the total outbound bandwidth was reduced from 320 KiB/s to 200 KiB/s, almost a 40% reduction. These Bloom filter responses (blue) are now replaced with Rate limited responses (yellow), which utilize almost no bandwidth.

Additionally, we observed that we are now rate-limiting the Bloom filters with a low hit-rate. We are now only responding to Bloom filters with a high hit-rate.

We expect MEV actors to adapt over time. Hopefully, they'll stop sending bad Bloom filters to maximize their limited queries. Regardless, the days of nearly unlimited pull gossip requests are over. DUN DUN DUUUUUUNNNNNNN

Reflections

This change didn't aim to reduce MEV on Avalanche. If you post a sloppy swap with wide slippage, you'll still get sandwiched. That's the nature of open, transparent blockchains (for now).

What it does is protect the network itself. Validators will no longer waste resources streaming their mempools to adversaries hundreds of times per hour. The gossip layer is back to working as designed: efficient and predictable.

These investigations are my favorite part of working on Avalanche. Sometimes, protocol development turns into a chess game played in code and metrics, with real money on the line.

Is this guide helpful?

Written by

On

Fri Sep 05 2025

Topics